Connecticut is moving ahead with an initiative to prioritize black and brown communities in the distribution of business licenses for recreational marijuana, which state leaders say will help remedy historic injustices.

Governor Ned Lamont, a Democrat, on Thursday convened the first meeting of the state’s Social Equity Council, which will help decide who can take part in the bonanza of legal weed.

Connecticut last month became the 19th state to legalize recreational marijuana, with sales set to begin next July, and the new law mandates steps to prioritize communities that were hardest hit by the war on drugs.

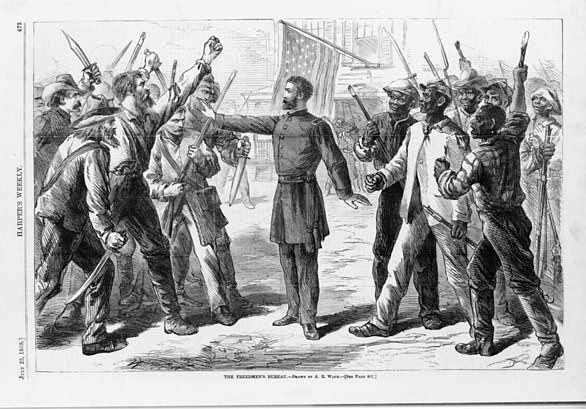

‘We’ll finally have, within the community of black and brown, a way to wealth creation. I think this is the opportunity to truly see the 40-acres and a mule of our ancestors,’ said Joseph Williams, UConn Small Business Development Center, at the council’s first meeting, WTNH-TV reported.

Connecticut’s Social Equity Council met on Thursday to begin setting rules for who will take precedence in licensing for newly legalized recreational marijuana

Governor Ned Lamont, a Democrat, vowed to ‘break down barriers for a lot of Black & Brown folks who have traditionally, and unfairly, not been given a seat at the table’

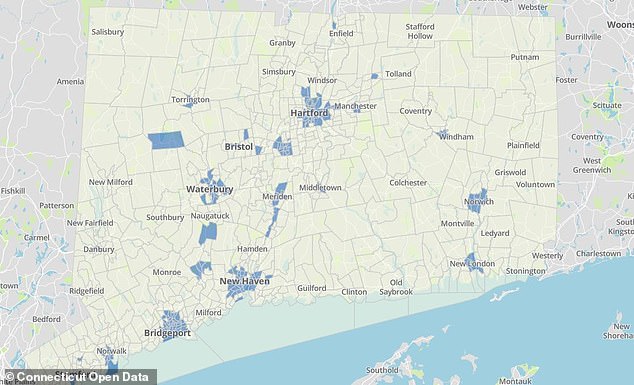

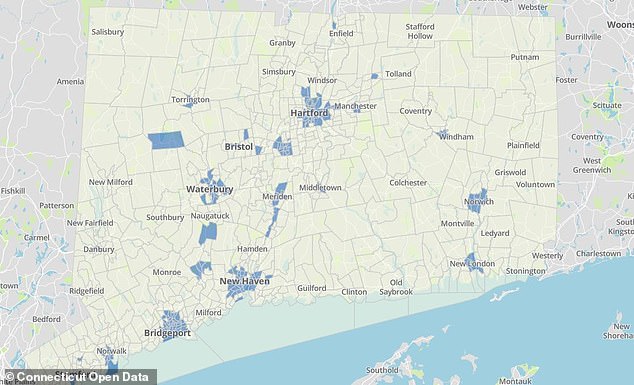

A map shows the ‘disproportionately impacted communities’ in Connecticut that were approved by the Social Equity Council for priority in marijuana dispensary licenses

The phrase ’40 acres and a mule’ refers to proposals following the U.S. Civil War to give land to freed slaves as a form of reparations. Such a program was implemented under President Abraham Lincoln but overturned by his successor Andrew Johnson.

In Connecticut, the goal of the Social Equity Council is to ensure that some of the economic benefits of legal weed go to communities disproportionately impacted by weed prohibition.

‘I grew up in one of those disproportionately impacted areas. Drugs have ravaged my family. Affected me personally. I could have been easily swallowed up myself,’ Avery Gaddis, a member of the council, told WVIT-TV.

At Thursday’s meeting, the council approved a map that designates 215 census tracks as ‘disproportionately impacted areas’ that will receive priority in the licensing process.

Together, the tracts account for 23 percent of Connecticut’s population, but are responsible for 67 percent of historical drug convictions.

The priority areas, which are mostly urban zones with large black populations, were determined by identifying census tracts with historical drug conviction or unemployment rates of more than 10 percent.

‘I grew up in one of those disproportionately impacted areas. Drugs have ravaged my family. Affected me personally,’ Avery Gaddis, a member of the council, told WVIT-TV

A growing operation is seen in Connecticut, which last month became the 19th state to legalize recreational marijuana, with sales set to begin next July

In addition to residing in one of these areas, social equity applicants must earn less than 300 percent of Connecticut’s current median income, which equates to roughly $114,000.

Under the new law, half of all cannabis licenses must go to equity applicants, who could also qualify for lower licensing fees, training and funding to cover startup costs.

‘It will be approximately $40 million a year that will go into this social equity fund,’ Governor Lamont said.

‘Not all folks come from communities have folks they can go to from friends and family. Well, we’re your friends and family right here,’ he added.

By the new cannabis law, the Social Equity Council must publicly post its final list of qualifications for social equity applicant by September 1.

Those priority applicants can begin submitting licensing forms 30 days later, and non-equity businesses can start applying 30 days after that, the law says.

Flags with a marijuana leaf wave outside the Connecticut State Capitol building in a file photo

Connecticut is not the first state to mandate equity requirements for its legalized weed industry.

Numerous other states have included similar requirements, with the most robust including California, Illinois and Michigan.

In Michigan, licensing fees are reduced for applicants living in ‘disproportionately impacted communities’, and like Connecticut the state aims to have at least half of all licenses go to equity applicants.

California assists cannabis license applicants with certain equity credentials with loans, grants and technical assistance.

Illinois awards a significant number of points in its recreational license evaluations to equity applicants, and charges existing medical license holders, all of them white men, steep fees that are used to fund generous loans and grants for their new equity competitors.