James Mollison never intended to end his solo transatlantic flight in New Brunswick.

The Scottish aviator was trying to fly from Ireland to New York non-stop in the summer of 1932.

He wanted to become the first to fly solo across the Atlantic “the hard way,” from Europe to North America, which meant fighting headwinds the whole way.

But as he headed south along the coast of New Brunswick after nearly 30 hours in the air, Mollison realized that New York was too far away.

Mollison’s plane in flight at Nerepis, NB, probably taken while flying from Pennfield to Saint John Airport. (Unknown/NB Museum Archives X12490)

“I went down the coast and then, well, my gas supply was so low that I knew I couldn’t get to my destination,” Mollison told Evening Times-Globe reporters who rushed to Pennfield, about 70 kilometers southwest of Saint John, after he landed.

“And I was all, tired as a dog, and when I saw this field, I decided to leave it.”

The field belonged to farmer James Armstrong, and the plane had come to rest in a patch of blueberries.

As the Times Globe put it on August 20, 1932, the day after Mollison’s landing, Pennfield “had suddenly and unexpectedly become the center of world news.”

Unlike the Pennfield farmers who greeted him, Mollison was no stranger to the spotlight.

Achieve fame

Born in Glasgow in 1905, Mollison learned to fly in the Royal Air Force in the early 1920s.

After brief stints as a flight instructor and commercial pilot, he decided to try to make a name for himself by breaking aviation records.

In the summer of 1931, he rose to fame by flying from Australia to England in a record eight days and 19 hours.

He followed this in the spring of 1932 with a record flight from England to Cape Town, South Africa.

Amy Johnson and James Mollison in front of the plane called The Heart’s Content at Stag Lane Aerodrome, London, on 16 August 1932, just days before their transatlantic flight. Johnson was probably a more famous aviator than her husband at the time. They had only been married for a few weeks. (AP Photo/Staff/Len Puttnam)

Amy Johnson and James Mollison in front of the plane called The Heart’s Content at Stag Lane Aerodrome, London, on 16 August 1932, just days before their transatlantic flight. Johnson was probably a more famous aviator than her husband at the time. They had only been married for a few weeks. (AP Photo/Staff/Len Puttnam)

But his place as the darling of the British press was probably cemented when he married Amy Johnson, an English aviator whose fame rivaled that of Amelia Earhart.

Attractive and glamorous, her marriage to Johnson, which took place just three weeks before her transatlantic flight, led the press to dub them “The Flying Sweethearts”.

Midge Gillies, the author of the biography Amy Johnson: Queen of the Air, said the pair shared an urge to test themselves.

“Well, I think they loved the fame,” Gillies said in an interview from his home in the United Kingdom. “And I think with Jim, the money was very important, the sponsorship, all the deals he could get… And I think once you do that, you’re hooked.

“And then there’s always a trip that’s a little more difficult, but you have to try. So it’s like a kind of drug, I think, and it gives you a kind of physical rush that we’ve forgotten that flying encompasses if you’re doing. – it in one of those really basic plans.”

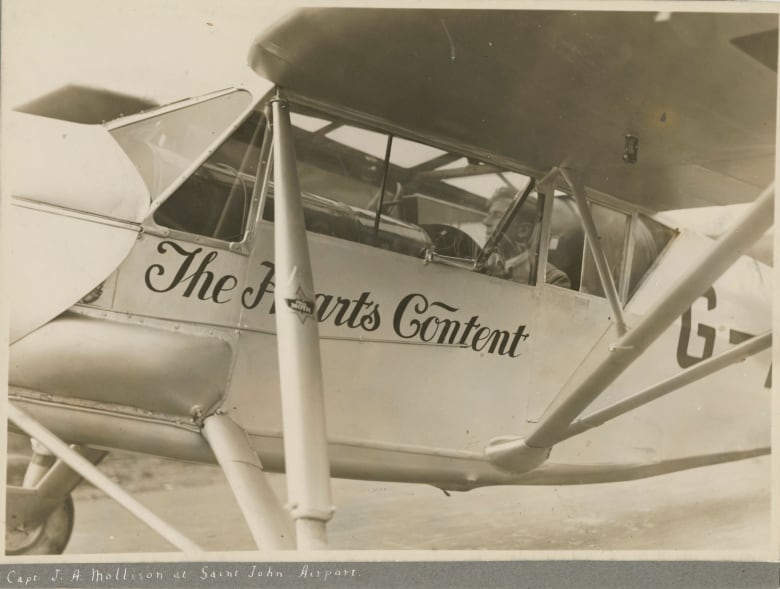

Mollison at the Saint John airport preparing to depart for New York. Note the large fuel tank that fills most of the front of the cockpit, a necessary modification to carry enough fuel to make the flight. (Unknown/NB Museum Archives X8734)

Mollison at the Saint John airport preparing to depart for New York. Note the large fuel tank that fills most of the front of the cockpit, a necessary modification to carry enough fuel to make the flight. (Unknown/NB Museum Archives X8734)

And the aircraft Mollison used was as basic as you could get in 1932. The de Havilland Puss Moth was a light aircraft made for the private market.

Capable of a cruising speed of around 175 km/h, it was not designed for long-distance flying, so Mollison had to modify it to carry as much fuel as possible, which included getting rid of of the radio

He described it as “a flying gas tank”.

She dubbed it “The Heart’s Content,” a reference to her marriage to Johnson that occurred just three weeks before the flight.

He took off from Portmarnok Beach, near Dublin, on 18 August 1932. The beach, several kilometers long, was chosen because it was long enough to give him time to board the heavily laden aircraft of charge

Gillies said the flight Mollison boarded was incredibly dangerous.

“When you fly from England and then you are [over] the Atlantic, touch the oncoming winds. And then you have to try to negotiate … the east coast of America or Canada when you’re more tired, so that’s probably one of the most imposing things you can try to do in your twenties or thirties,” he said.

“It really kind of pushed the skill of the pilots, but also the endurance of the plane. And if you think about it, if you went down, you had very little chance of saving yourself unless you were lucky enough to be there . a shipping lane and see a ship there.”

fly blind

Mollison took off in torrential rain at around 10:35 a.m. Irish time, but had a weather forecast that said he would be flying in clear weather.

This turned out to be only partly accurate.

He had favorable conditions for most of that day, but as night fell he ran into heavy fog.

Mollison attempted to climb it, but the weight of the fuel on board prevented the plane from climbing more than 4,000 feet.

“When it’s clear, you can tell how the wind is blowing from the breakers below you,” Mollison told reporters.

“Although I couldn’t see the water at all and just had to walk. I was lucky. When the dawn broke this morning, I wouldn’t have been at all surprised to find myself over Labrador.”

Instead, using only a compass, a watch and his airspeed indicator, and allowing for a wind drift he had estimated at seven percent, Mollison had set over the Avalon Peninsula near Harbor Grace, almost exactly where he had expected to be.

Perhaps something he did during his RAF days played a role in helping him break through the fog.

Gillies said Mollison used to drive from London to his nearby base at night and turn off his headlights during the journey.

“He later said that it really helped him fly across the Atlantic because he was flying blind. Because you often have no idea where you are, you have to really believe in yourself.”

A few quick photos

After flying low over Halifax and Saint John, his decision to settle at Pennfield at 12:45 local time created an international sensation.

It had been in the air for 30 hours and 10 minutes.

After posing for photographs at the landing site and meeting with the provincial Minister of Health and Labor, Henry I. Taylor, who came to view the plane from his nearby home, reporters taken to Saint John and taken to the Admiral Beatty Hotel. .

A signed postcard of a photo taken at Pennfield shortly after Mollison touched down, now in the collection of the New Brunswick Museum. (Louis Merritt Harrison/NB Museum Louis Merritt Harrison Collection 1989.83.317)

A signed postcard of a photo taken at Pennfield shortly after Mollison touched down, now in the collection of the New Brunswick Museum. (Louis Merritt Harrison/NB Museum Louis Merritt Harrison Collection 1989.83.317)

The following day’s paper covered the event, with an extensive interview with Mollison.

In it he revealed that the only food he had brought with him on the flight was a handful of barley candy and two miniature bottles of brandy.

He also regretted his decision to give up his radio to save weight.

“But I’ve learned the great need for wireless equipment,” he said. “It is as essential as a good compass. It removes the element of doubt from the mind.

“You can imagine nothing more disconcerting than to be out of touch with the world.”

If he had had 10 more gallons of fuel, he said, he would have made it to New York City.

He would fly to New York on August 22, and the news of the day would make only a passing reference to his landing in New Brunswick.

Loves no more

Mollison would make other notable flights in the early 1930s, including flying across the Atlantic with his wife.

But it wouldn’t be long before his demons began to catch up with him.

The only child of an unhappy marriage that ended in divorce, Mollison apparently inherited his father’s predilection for alcohol abuse.

And his glamorous wife’s continued success as a flyer, including breaking his speed record in Cape Town, took its toll on his fragile ego.

Gillies said it wasn’t long before the Flying Sweethearts experienced marital turmoil, even as they attempted record flights together.

“They used to have a terrible fight in the cabin and, you know, it must have been terrible,” he said.

“I think it’s a battle of two very independent people who are used to flying solo and suddenly they meet another pilot and who they’re married to, you know.”

Mollison and Johnson argued for much of a flight they took from England to New York in the summer of 1933. The flight ended in a crash landing and both suffered minor injuries. They marked their first wedding anniversary with American aviator Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Palmer Putnam in Rye, NY From left to right are Putnam, Earhart, Johnson and Mollison. (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Mollison and Johnson argued for much of a flight they took from England to New York in the summer of 1933. The flight ended in a crash landing and both suffered minor injuries. They marked their first wedding anniversary with American aviator Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Palmer Putnam in Rye, NY From left to right are Putnam, Earhart, Johnson and Mollison. (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

By 1936, their marriage had ended. They divorced in 1938.

“I think it was very attractive to him in the beginning to be with a woman who was more successful than him in the beginning,” Gillies said. “And aviation at that time was all about contacts, who you knew, who you could get sponsorship from, so it was helpful for him to have Amy Johnson on his arm.

“But then, as he became more successful as a driver, there was a real rivalry between them.”

Both Mollison and Johnson served in World War II, transporting new aircraft to the UK

Johnson died in January 1941, when the plane he was flying apparently ran out of fuel.

A sad ending

Mollison ran a pub and then a hotel after the war, but alcohol had taken its toll. In 1953, his pilot’s license was revoked due to his drinking problem.

He died in 1956 in a mental health hospital from the effects of alcohol abuse.

Gillies said Mollison was a flawed character, and probably gay, but there was no doubting his bravery in what was a dangerous way to make a name for yourself.

“They were really big stars. But there was always the feeling that that could go away and that you were only as famous as your last flight.”

And in his effort to find that prominence, Mollison inadvertently brought the world’s attention to New Brunswick.