Taleem dadaan, sawaab daddar. At a “secret school” in a Kabul neighbourhood, a girl writes out the Dari sentence on a whiteboard in the Persian script. “Give education, earn virtue.”

The underground school in suburban Kabul began in July this year, one of 50 set up by women’s rights activists, months after the Taliban regime in Afghanistan disallowed school for girls studying in classes 7 and above. In the Taliban’s interpretation of Islam, there is no sawaab in educating girls. While women have so far not been stopped from going to universities — men and women go on separate days — given the ban on schooling, there will be no new admissions.

In the class of 26 are women of varying ages, including a woman in her thirties, who had to drop out of school in her fourth grade during the first Taliban regime from 1996 to 2001, and her daughter, who should have started Class 8 in March this year but is now out of school — two generations of women who know first-hand what it is to have dreams cut short, what it is for women and girls to live under the Taliban’s boots.

“I could never go back to school after that. I come here because it is a chance to relearn how to write and read Dari and be able to do some sums, so that I can teach my children,” says the mother.

Her daughter says she finds the class too basic, but “I don’t want to forget what I have learnt in my school. Plus, I get to meet other girls here, like I used to in school. It is more fun than staying at home.” She wants to be a teacher when she grows up. Another girl her age wants to be a nurse.

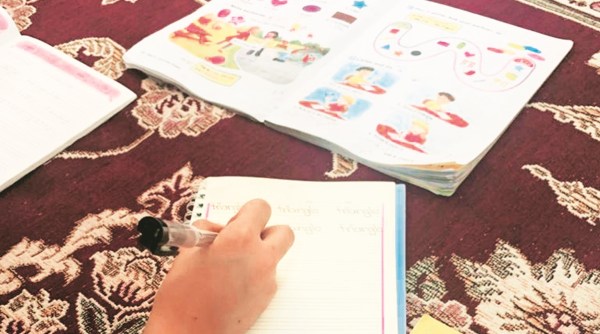

At an underground class in Kabul, among the many that have come up since the Taliban banned girls higher than Class 6 from school. (Express Photo by Nirupama Subramanian)

The school is held every afternoon from 3 pm to 5 pm in the first-floor home of a midwife, who has an undergraduate degree in education. A fridge with fruit magnets has been pushed aside to make space for the girls, who sit hunched on a carpet. A drum helps prop up the whiteboard. They learn to read and write Dari (in Persian script) and memorise multiplication tables.

“When we first started, there were a few girls, but the word spread and it looks like I will soon have 40 girls and women here. I might need to start another class,” says the teacher, who worked at the UN as a community outreach person but found herself without a job after the Taliban took over in 1996.

Women and girls were among the first sections of the Afghan population to be directly impacted as the Taliban returned to rule the country on August 15 last year.

In a report in June this year, the UN documented a series of restrictions on Afghan women since last year that have curtailed their freedoms and rights. After the formation of an all-male cabinet, the first ominous signal came when the Ministry of Women’s Affairs was replaced with the Ministry for Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. Since then, a number of edicts have followed — prescribing dress codes for women in public and for women television journalists, and rules on the mobility of women. It is now compulsory for a woman to be accompanied by a mahram — a male family member — when travelling beyond a radius of 78 km.

Working women, including those in the government, have been asked not to come to work. Many have lost their jobs, some are allowed back on one day of the month, and some once a week, but only to sign the attendance register. For this, they receive a reduced salary.

At an underground class in Kabul, among the many that have come up since the Taliban banned girls higher than Class 6 from school. (Express Photo by Nirupama Subramanian)

At an underground class in Kabul, among the many that have come up since the Taliban banned girls higher than Class 6 from school. (Express Photo by Nirupama Subramanian)

Only the teaching and health sectors have been spared. Women also continue to work where their presence is considered necessary by the Taliban — most noticeably, in the police and in airport security, where woman passengers need to be frisked. In workplaces where women continue to work, they have been segregated from their male colleagues.

In Kabul, young girls walk, books clutched tight against their black-clothed bodies, to attend private English coaching classes known as “course”. This is the only kind of education now allowed for teenage girls, other than “Islami” education at madrasas.

Sometimes women can be spotted walking in a park in the morning, in groups of three or four, covered head to toe in black. Some parks have designated days for men and women, and some, like the famous Bagh-e-Babur, have separate gendered sections.

While a large number of women have been rendered invisible already, the silver lining is that they have refused to disappear fully from public spaces. They cover themselves in the prescribed dress code, and try and continue their lives as best as they can.

A woman waits for a friend by the roadside, looking anxiously into her phone. In less affluent areas, women are out shopping for vegetables and fruits at roadside markets. And the number of women begging on the streets, children in tow, has gone up so much that the Taliban have announced they are going to round them up.

On a Friday, the weekly holiday, a group of women, all from one family, along with their children — all of them girls — sit around a long table in a restaurant. The introductions that go around the table offer a brief glimpse into how the lives of middle-class, educated Afghan women have been affected by a year of Taliban rule.

“We have come out like this after a long time… nearly six months. It has been a depressing time for everyone, especially the girls. They can’t go to school anymore,” says Nadia Shokuri, a doctor working with an international NGO that has projects in Nuristan, Nangarhar, Paktia, Ghazni and Kunar provinces of Afghanistan.

“I have to travel to supervise field work. I am really happy with the work I do, but now the problem is, we cannot go to far-off places without a mahram. I take my husband. But he does not like to come with me all the time because he has his own job. That is why now I go only once every two or three months,” she says.

The mahram rule has seen many international organisations and their local partners, which have tried to retain most of their women employees, hiring married couples.

Ismatullah Kohistani has been working in the government department of museums since 2003, and is posted at the National Museum of Afghanistan. “I still work there, but only in name. They have asked us not to come. Once a week, I go and sign the register and I get my salary,” she says.

Marwa Kohistani used to work in a court. “After the Taliban came, they fired all women. I have specialised in Shariat law, I studied it as part of my LLB course. Right now, I’m not working and mentally, that doesn’t feel good,” she says.

Maliha Kohistani is a teacher in a girls’ school, which does not have classes any more for Grades 7 to 12. She teaches classes 1 to 3. “Our problems are too many,” she says, adding that the security situation in Kabul has, however, improved. “Earlier, we wouldn’t have been sure about stepping out like this.” Others around the table disagree loudly and arguments break out.

The three teenage girls at the table now no longer go to school. One wanted to become a doctor, another a clothes designer, the third a businesswoman. They believe they can pursue their dreams only if they go abroad.

Everywhere in Kabul, the sense of siege is palpable. Nearly everyone is waiting to leave for any country that will take them. Many educated Afghans have already left. With several embassies yet to reopen after shutting down last year, thousands have left for Pakistan to apply for visas from there. India recently opened its embassy in Kabul, but is not issuing visas.

Women living outside Kabul have it much tougher. A 19-year-old from a provincial capital relates her experience of being hauled off to a police station for being out with her 18-year-old nephew, her elder sister’s son. “It was the worst thing that ever happened to me,” says the girl, who is now in Kabul, waiting for a visa to a Central Asian country.

The girl recalls how she and her nephew were questioned separately to see if the names of their family members matched, but were still disbelieved. The Taliban at the station wanted the girl’s father, who lives in another province, to show up, but eventually agreed to meet the boy’s mother, who vouched that the girl was her sister. But even she needed a male witness to corroborate her statement.

“At the police station, the Taliban were calling me all sorts of names. When I started explaining, they ordered me not to speak. They said hearing my voice was haram for them. They told me not to look at them but they were staring at me like hungry lions. My hands were trembling, but I did not cry because that is what they wanted to see, a weak woman. My parents have taught me to be strong,” she says.

Abdul Qahar Balkhi, the suave English-speaking spokesperson at the Foreign Ministry of the de facto Taliban government, dismissed international concerns over women’s education and their near-banishment from national life as “incorrect” and “simply not true”.

He reels off numbers — 120,000 women work in the civil service, 96,000 of them in the education sector alone. “All of them have returned to work. All of them are going to their jobs daily, providing education to students,” he says.

The health sector has 14,000 women and they, too, have returned to work, he claims. Same with those employed to handle security assignments.

“They are working in passport offices and immigration and a lot of other areas. A very small number of women have not returned to work. However, they haven’t been fired, they are getting their salaries. Yes, the salaries are reduced, but that is for everyone. The budget of Afghanistan is such that we cannot pay the large salaries that were paid before we came to power. In the private sector, women are in business, they are shop owners. The government reopened the Women’s Chamber of Commerce in Kabul, Mazar-e-Sharif and Herat. They are working with NGOs, they are working in banks, and in other areas of the private sector,” he claims. “So this idea that women are not allowed to contribute is simply not true.”

Girls have access to secondary education in more than a dozen provinces, he claims, adding that in Kabul and other provinces, there is a “temporary suspension”.

“It is the only country in the world that has gone through 43 years of unremitting and incessant violence and conflict and occupation. There are cultural and budgetary constraints, then there is a lack of resources, infrastructure, teachers, books. But the government is working extremely hard to try to address this problem,” says Balkhi. “Our policy is education for all Afghan citizens, irrespective of gender.”

If the international community “genuinely” wants to help Afghanistan, says Balkhi, it should “not weaponise this issue, and can very easily assist Afghanistan in those areas that are open for them to assist”. Then, as the government continues to work to address the remaining problems (in education), “help it, instead of trying to find moral justifications for some of the very inhumane actions that they are taking, such as the sanctions on Afghanistan, freezing of assets, and the blacklist. So there’s work to be done by both sides”.

Dismissing the suggestion that the Taliban were insecure about empowered, educated women who might challenge their interpretation of Islam, Balkhi says, “The women of Afghanistan are Muslim, they don’t challenge our beliefs. Human societies are such that people have different views on different laws. But at the end of the day, it’s the government that enacts those laws.

Devastated by decades of war, school and college education in Afghanistan, particularly that of girls, was in critical condition even before the Taliban took over last year. Between 2002 and 2020, the country made small strides in education, but the effort was stymied by the war between foreign forces and the Taliban.

In a report earlier this month, UNICEF said even before the Taliban takeover last year, 4.2 million Afghan children were out of school, of whom 60 per cent were girls. Only 4.2 per cent of girls are in tertiary education, compared to over 14 per cent for boys. In a report in June, the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan warned that unless the Taliban allowed girls access to secondary education over the next two or three months, an entire generation of girls was at risk of not being able to complete their full 12 years of basic education.

Asked if as a Pashtun, he supported the Taliban (they are mainly Pashtun), a taxi driver with nine children — five girls and four boys — said, “What have they done for me that I should support them? Let them first allow girls to go back to school, then I will be the first to come out on their side.”

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

A woman activist is scathing about the “Great Game” that the US played on the people of her country. “America does not want peace in Afghanistan, that is why they handed over the country to the worst people. Violence allows them to keep control over Afghanistan,” she says. “Afghanistan is in such a place that everyone wants a piece of it. Unfortunately, the Afghan people are the most affected. Each time they pick themselves up and start anew, only to be hit again.”

In another underground school in a Kabul neighbourhood that has experienced many bombings, a 16-year-old girl, who was in Class 11 when the Taliban took over, says she has given up her dreams of becoming a doctor; she now teaches English to girls in her neighbourhood. Several of her students are in classes 1 to 6, and they come to learn from her after school hours. The girl shows the school uniform she had worn until last year — black tunic and trousers, with a white scarf.

One of her students would have been in Class 8 this year. “We were so happy to go to school when it opened on March 23 (the school academic year is from March to January). But when I reached, the school head told us to go home. One of my friends even said she was ready to come to school in a burqa, some were crying,” the girl says. “My biggest fear that day was that I would become illiterate. I want to be a nurse when I grow up, and that cannot happen until I can study and go to college and university.”