Former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan has condemned the attack on Salman Rushdie, calling it “horrific” and “sad” and saying that while the Islamic world’s anger over Rushdie’s book The Satanic Verses was understandable, it was not could justify the assault. .

Khan also said he hoped Afghan women would “assert their rights” in the face of Taliban restrictions in an interview with the Guardian in which he sought to temper his fiery reputation. He is fighting for his political survival after being removed from office in April. Khan says his staff and supporters are being harassed and intimidated and that he is fighting eight-year-old charges of illegal campaign financing that could see him banned from politics.

Ten years ago, Khan pulled out of an event in India because Rushdie was also due to appear and the two men exchanged insults, but Khan does not appear to have expressed support for violent action against the Indian-born author. India His denunciation of the attack is surprising, however, in a region where most politicians have shied away from comment.

Asked for his response to the knife attack in New York state that left Rushdie badly injured, Khan said: “I think it’s terrible, sad.

“Rushdie understood that, because he came from a Muslim family. He knows the love, the respect, the reverence of a prophet who lives in our hearts. He knew that,” Khan said. “So the anger I understood, but you can’t justify what happened.”

“The Afghan people will claim their rights”

A year ago, Khan caused consternation in the West and many Afghans when he welcomed the Taliban’s seizure of power, saying it was “breaking the chains of slavery”. She defended the Taliban’s treatment of women and girls, describing it as a local “cultural norm” and noting: “Each society’s idea of human rights and women’s rights is different.”

A year later, women remain excluded from the Afghan workforce and girls over 14 are still banned from school. Khan, however, insisted that change had to come from within Afghanistan.

“Finally, Afghan women, the Afghan people, will claim their rights. They are strong people,” he said. “But if you push the Taliban from the outside, knowing their mentality, they’ll just put up defenses. They just hate outside interference.”

Since losing a no-confidence vote in April, Khan said his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), had been the target of efforts by the new government and security forces to out of the political scene.

One of the top aides, Shahbaz Gill, was arrested on Tuesday and was hospitalized while in custody. Khan said he was beaten and “psychologically broken”.

Islamabad police said Gill was arrested for inciting citizens against state institutions and “inciting people to rebellion”. Khan said Gill was targeted because he had said army officers should not obey illegal orders.

“They are forcing him to say that I was the one who told him to say it,” the former prime minister said.

A medical report on Gill said he had arrived at the hospital with rapid breathing, noting that he was asthmatic. He also referred to “body aches” and “soft tissue tenderness” in his arm, lower back and buttock. It was reported that he had been released from the hospital on Thursday afternoon and was back in custody.

The TV channel that interviewed Gill before his arrest, ARY, has been shut down in parts of the country.

Khan said Gill’s arrest and the closure of ARY were part of a pattern under the current government of Shehbaz Sharif, who replaced Khan as prime minister.

“What they’re doing to Gill is sending a message to everybody,” he said. “And they have scared our workers. Social media activists have been picked up and we have very vibrant social media. They’re trying to intimidate people.”

Pakistan also had a poor human rights record under Khan from 2018 to April this year, with extrajudicial killings of dissidents and frequent threats against journalists, particularly journalists who suffered torrents of sexual abuse in social networks.

Khan blamed the excesses and disappearances on counterinsurgency tactics by security forces.

“They were in charge of collecting people, but according to them they were involved in this insurgency, which was happening in Balochistan and the tribal area bordering Afghanistan. So they would blame it, with some justification, because you couldn’t convict terrorists in court because you don’t get witnesses,” Khan said.

“In my time, we never tried to suppress the media. The only problem was that sometimes the… security agencies, three or four times we found out that they picked someone up and immediately when we found out, we would release them right away,” he said.

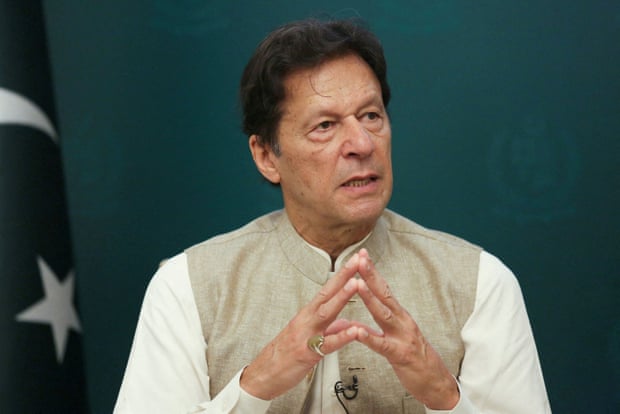

Pakistan’s former prime minister Imran Khan blamed security forces for human rights abuses during his reign. Photograph: Saiyna Bashir/Reuters

Free press advocacy organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said the litany of abuses under Khan’s government was “endless”. But he added that there was a new campaign to intimidate critical journalists.

“There has been no break in the harassment of journalists since Khan was replaced by Sharif as prime minister, quite the contrary,” RSF said in a statement.

Khan is also facing a case against the PTI by the country’s election commission for illegal foreign campaign contributions. He did not deny the allegations but dismissed the case as politically motivated, saying rival parties such as Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) had not faced similar scrutiny.

One of PTI’s founding members, Akbar Babar, filed a case against the party in November 2014, alleging irregularities in the handling of approximately $3 million in foreign funding. Last month, the Election Commission of Pakistan ruled that the PTI had received prohibited funding. The Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) has been tasked with further investigating and the commission summoned Khan on Tuesday. Experts say Khan may be banned from politics or his party banned if the charges are proven.

Khan blamed Washington for engineering the no-confidence vote that brought down his government, suggesting the US had helped persuade members of his party to defect.

He also blamed the Pakistani military, which has long acted as a kingmaker in the country’s political life. He was more circumspect about blaming the security forces in his interview with The Guardian, but said: “If they weren’t behind the conspiracy, surely they could have stopped it because the intelligence agencies, the ISI [Inter-Services Intelligence] and ME [Military Intelligence]they are international quality intelligence agencies and would certainly have known what was going on.”